Updated 10 months ago

Are solar leases and PPAs making a comeback in 2023?

Written by

Ben Zientara

When it comes to solar panel financing, times are hard. Interest rates are higher than they’ve been in years, and dealer fees are increasing, creating higher costs for homeowners. Loans can still be a good way to pay for solar panels, but the current economic climate has diminished their advantage.

At the same time, new tax credit adders for solar businesses make it much more financially attractive to build and maintain solar installations rather than just sell them. Solar-as-a-service companies like Sunrun and Sunnova stand to benefit greatly from these incentives, as they’ll be able to offer their long-term agreements on more agreeable terms than ever before.

Below, we’ll look at the differences between the kinds of solar ownership, why owning solar panels is usually considered preferable to leasing them, and how current events may be changing that dynamic.

Key takeaways

-

Third-party ownership, or TPO, is a way to get solar panels on your roof that you then lease for a monthly fee or agree to purchase the power output from over a period of time (usually 20 years).

-

Third-party ownership is usually designed so the customer has zero out-of-pocket cost and saves a small amount on their electricity bills each month by paying the solar company instead of the utility for a portion of their energy needs.

-

Conventional wisdom says it is better to own your solar panels, but leases and PPAs can work well for people who can’t take advantage of certain tax incentives and plan to be in their home for several years.

-

Third-party ownership could be getting cheaper soon due to increased business tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act that will repay some of the cost the service providers incur when installing these systems.

-

As you shop for solar, look carefully at all the options for paying for solar panels, and judge them for yourself based on ROI, net present value, and intangibles like long-term warranties and service contracts.

The basics of solar ownership

There are several ways for homeowners to pay for the solar panels on their roof. They fall under two general categories: self-ownership and third-party ownership.

Self-ownership

Self-ownership is fairly straightforward: you pay for a solar installation with cash or a loan. The solar panels are your property, and you can do what you want with them. They add value to your home (as long as they’re paid off), and you get all the tax benefits and other solar incentives involved (as long as you can take advantage of them).

People who choose to finance their solar installation with solar loans commonly end up with a term of between 10 and 25 years, with an APR that can range from 0% to close to 10%.

These interest rates depend on several factors, but one of the major ones is an unseen “dealer fee” that the lending companies charge the solar installer when the loan is initiated. These dealer fees are passed along to the customer, increasing the principal of the loan over what a customer who paid cash would get. More on this later.

Third-party ownership

Third-party ownership, or TPO, is a bit more complicated, but the two basic types are solar leases and power-purchase agreements (PPA). These arrangements are contracts between you and a solar service provider who owns the panels. They don’t completely take the place of your utility company, but they can offset a significant portion of your utility bills with solar energy and, ideally, save you some money.

TPO is good for the service provider because it allows them to receive tax benefits and other incentives for solar power while also getting paid by their customers for the solar system. Scrupulous TPO providers factor those incentives and savings into their costs and design agreements to save customers money on solar from day one.

We won’t get into the intricacies of TPO here, but the basic rules are these:

A solar lease has a fixed monthly payment no matter how much energy the system generates. Usually, it comes with a guarantee that the energy will exceed a pre-set minimum. The annual cost of the lease is generally a little lower than the savings generated by the system.

A solar PPA is a contract to purchase all the energy the solar installation generates at a predetermined cost per kilowatt-hour (kWh). This cost is generally equal to or less than the cost of electricity from the utility company, so the homeowner saves a little bit of money on every kWh.

Both leases and PPAs sometimes come with an escalator clause, which states that the lease's monthly payment or the PPA's per-kWh price will increase by a small amount per year (usually between 1.5% and 3%). Choosing a lease or PPA with no escalator clause is more advantageous, but these clauses are very common and do not necessarily make it a bad idea to sign a TPO agreement.

You can read more about solar leases and PPAs if you need more background.

Conventional wisdom about solar ownership

Conventional wisdom says owning your solar panels is better than leasing them from a service provider. If you can take advantage of incentives like the federal solar tax credit, self-ownership should offer you the greatest financial benefit. Even if you take a loan for the system, you have options when it comes to paying it off early or rolling the remaining balance into a home refinance.

If you choose a lease or PPA instead, you’ll sign a contract (typically for 20 years) to get a portion of the energy you use from solar panels. You’ll pay a monthly fee that is hopefully lower than the cost of the utility bill it partially replaces, and you’ll get lifetime maintenance, performance monitoring, and warranty service from the solar company.

Certain challenges come with signing up for a solar lease or PPA:

You’ll be tying yourself to a service provider for 20 years, so you better pick a good one.

If you want to sell your home, you have to find someone willing to take on that contract.

If the electric bill savings from a third-party-owned system are minimal, it can decrease your home’s value in the eyes of buyers.

But there’s a funny thing about conventional wisdom: it doesn’t always work in unconventional times – and our times are far from conventional when it comes to financing.

Financing costs are out of control in 2023

Between March 2022 and May 2023, the Federal Reserve raised the target federal funds rate nine times, from almost zero to over 5%. Experts expect the May increase will be the last one of 2023 and that the Fed will keep rates that high through the end of the year.

Those interest rate increases have wreaked havoc on the solar industry by forcing lending companies to increase the dealer fees and APRs they charge to initiate solar loans. Top solar lending companies like Mosaic, Sunlight Financial, and Dividend have all updated their agreements with solar installers because of the Fed raising interest rates.

Respondents to our 2022 Solar Industry Survey indicated that the best deal they got from lenders in early 2023 was a 20% dealer fee and a 5% APR for a 25-year loan term.

More recently, anecdotal evidence from around the industry suggests that some lenders are charging up to 40% dealer fees to initiate a solar loan. Again, those fees get passed along to the homeowner in the principal balance of the loan.

Think about that: if you buy a home solar system with a solar loan today, the principal of the loan will likely be 20-40% more than the cost for someone who pays cash. If the average cash price of a 6-kW solar system is $18,000, the principal of a loan for that system might end up between $21,600 and $25,200.

Analyzing the effect of increased finance costs

Those increased costs don’t inherently make solar a bad financial investment – they just make it worse than before the interest rate hikes.

When calculating solar panel ROI, the ideal way to gauge performance is a metric called “Net Present Value,” or NPV. The basic idea is that money in your pocket today has value because you could invest it and get a return.

If you use that money to purchase solar panels instead, you can examine the value of future energy bill savings to see whether spending the money on solar is better than investing it in another way. The historical average return of the stock market is 7.8% per year, which is often used as the rate to compare to NPV calculations.

Example solar savings calculations

Let’s look at an example. Say you live in a state with electricity prices at about the national average of $0.15/kWh, and you use about 7,800 kWh per year. That’s a bill of about $100 per month.

A 6-kW solar installation would generate about that much electricity in a year, and at the average cash price in 2023 of $2.95/watt, the total upfront price would be $17,700. The federal solar tax credit would knock that down by 30%, so your final year one cost for solar would be $11,220 (That’s $17,700 minus the $5,310 tax credit, minus the $1,170 in energy savings).

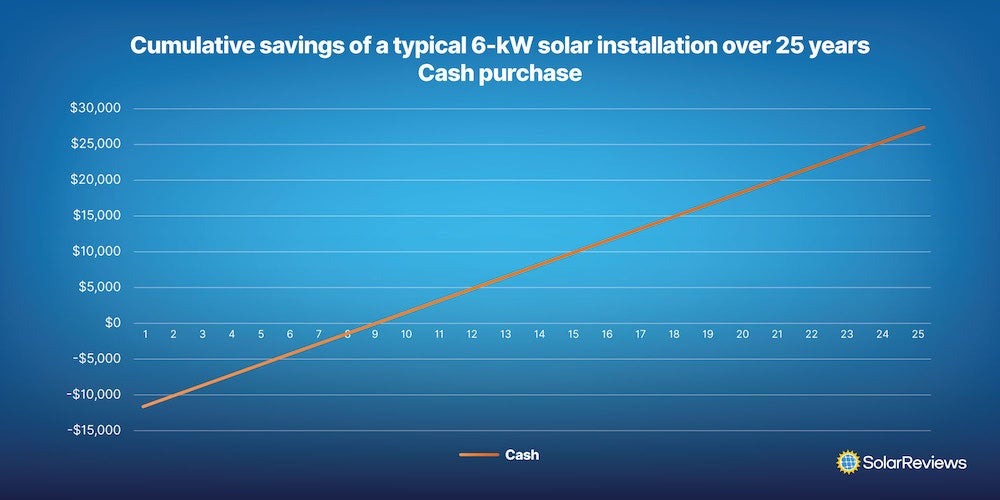

Every year, the savings would increase a little as the cost of electricity rises every year. You’d end up paying back the system's initial cost after about 9.5 years, and the total savings would be a little over $27,000 in 25 years.

The NPV of this investment is about $4,275. That means the promise of future savings is worth $4,275 more than if you invested the same amount of money in an index fund that earned 7.8% for 25 years.

Here’s how that looks on a chart:

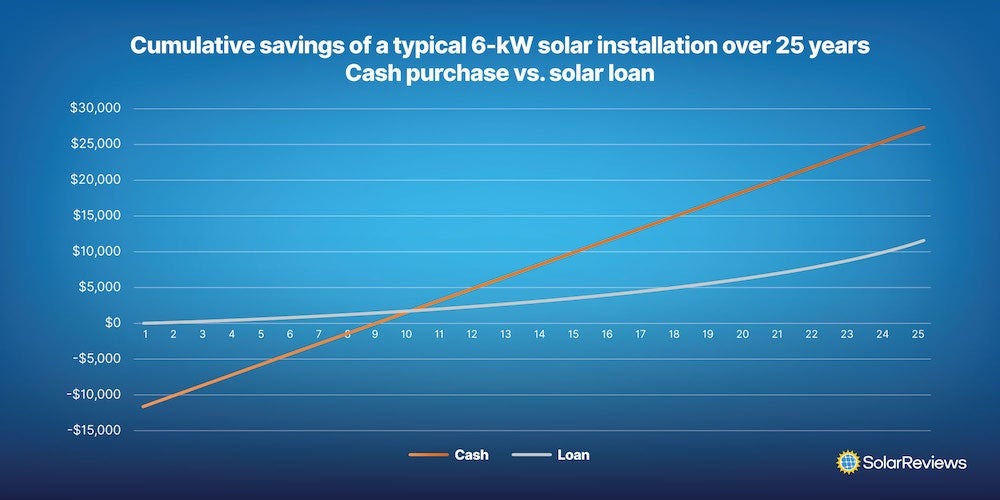

If you took a loan instead, you would start with zero out-of-pocket cost. On a 25-year loan with a 40% dealer fee and a 4.49% APR, the loan payments would be about $96.50 per month, but you’d save an average of $97.50 per month on electricity.

That’s a net savings of $12 in year one. Not very much, but you didn’t have to plunk down your own $17,700 to pay for the thing, right?

Again, the savings would increase yearly as utility costs get more expensive. Here’s how the loan looks compared to the cash purchase:

The loan’s total amount saved is much less because you’re making the loan payment the whole time, but you still end up with positive cash flow. The NPV of $3,215 for the loan is smaller than cash, but not by a ton, because you’re not tying up a large amount of money in year 1.

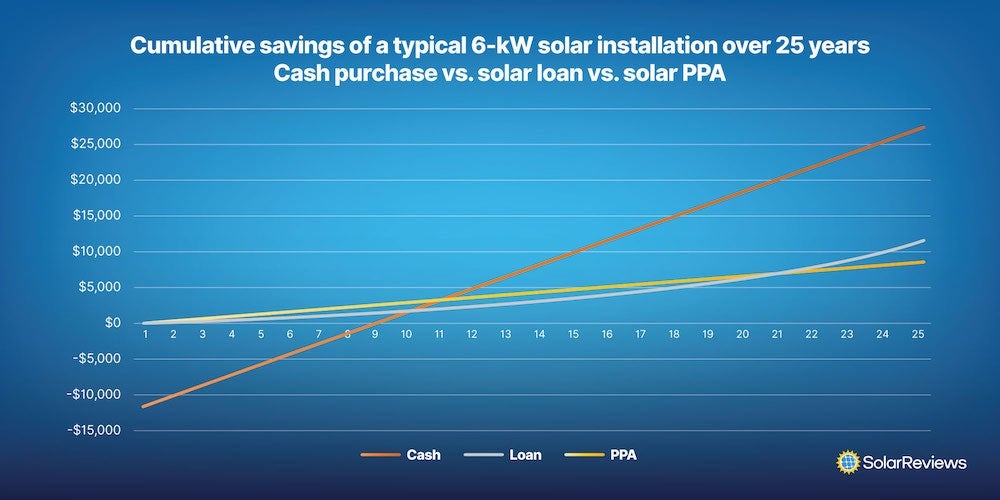

Now let’s look at a PPA. Let’s say you can get one for $0.12/kWh, with an escalator of 2.9% per year. That’s not much cheaper than what the utility is charging you, but it already produces a savings of $0.03/kWh, or $234 per year.

As the years go by, the PPA should keep saving you money as long as the cost of grid electricity rises by at least 2.9% per year. The $0.12/kWh PPA’s Net Present Value in this scenario is $3,268, which is almost exactly the same as the loan.

We promise this is the last chart:

Now let’s discuss why leases and PPAs might soon become more advantageous.

Lease and PPA providers can take additional incentives thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act

The examples above are just examples, but the numbers used in them are fairly close to real-world solar purchases. Cash may still have the best NPV and give you the freedom to do whatever you want with the panels, but leases and PPAs might be getting cheaper soon, bringing good solar deals to people who can’t take the tax credit on their own.

New provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) allow commercial businesses like solar service providers to take a larger tax credit than homeowners can. Tax credit adders in the IRA can net these businesses an extra 10 to 40 percent of the cost to install solar.

Such a major reduction in their costs will no doubt cause some enterprising solar service providers to reduce the cost they charge their customers for PPAs and leases, thereby making third-party ownership more attractive to homeowners.

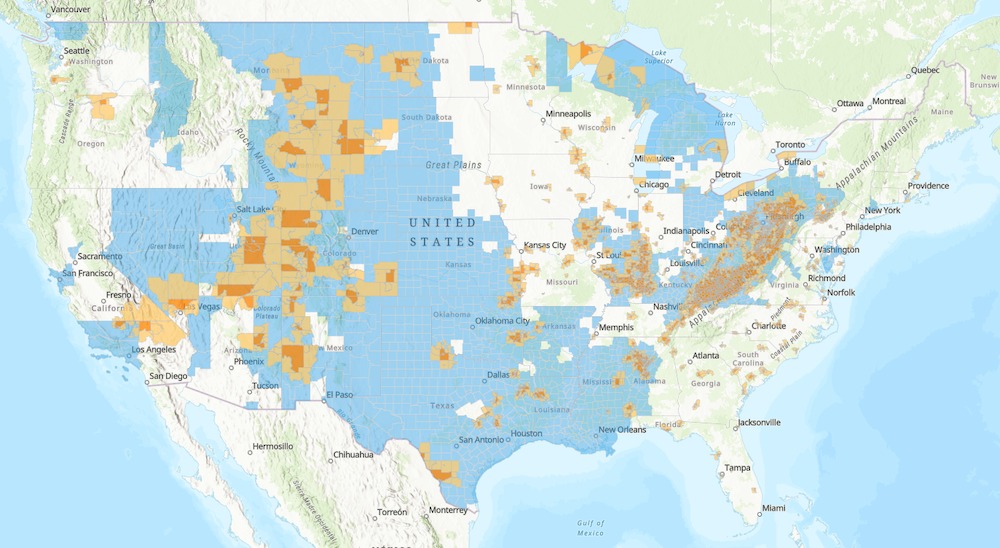

Some of the adders are tied to installations completed in “energy communities,” which are places near old fossil fuel plants or where people are transitioning away from employment in the fossil fuel industry. This could mean a blossoming of reasonably-priced PPAs and leases in states where solar doesn’t enjoy broad governmental support.

Businesses that install solar panels in any of the blue or orange areas get a bonus 10% tax credit, and maybe more. Image: Department of Energy

If you live in one of these communities, be on the lookout for these offerings, and be ready to spot a good deal from a bad one.

How to choose the right provider

There are a few steps to finding a great solar installer:

Learn as much as you can about solar panels for homes

Estimate the system size you need, along with the potential cost, incentives, and savings, using our free solar calculator

Get in touch with at least three local solar installation companies, compare the quotes they provide, and choose whether to select one for your project

Reviewing more than one solar quote before deciding to proceed with a solar installation is vitally important. You can see differences in how installers estimate the energy production and savings provided by solar panels and get a sense of their commitment to care for you during and after the installation process.

Different installers offer different equipment, pricing, warranties, and additional services like EV charger and battery storage installation. It’s a good idea to review the various options in your local area and talk with your trusted financial advisor before proceeding.

Ben Zientara is a writer, researcher, and solar policy analyst who has written about the residential solar industry, the electric grid, and state utility policy since 2013. His early work included leading the team that produced the annual State Solar Power Rankings Report for the Solar Power Rocks website from 2015 to 2020. The rankings were utilized and referenced by a diverse mix of policymakers, advocacy groups, and media including The Center...

Learn more about Ben Zientara