Updated 1 week ago

What is net metering and how does it work?

Written by Ben Zientara Ben ZientaraBen Zientara is a writer, researcher, and solar policy analyst who has written about the residential solar industry, the electric grid, and state util...Learn more , Edited by Catherine Lane Catherine LaneCatherine has been researching and reporting on the solar industry for five years and is the Written Content Manager at SolarReviews. She leads a dyna...Learn more

Why you can trust SolarReviews

SolarReviews is the leading American website for solar panel reviews and solar panel installation companies. Our industry experts have a combined three decades of solar experience and maintain editorial independence for their reviews. No company can pay to alter the reviews or review scores shown on our site. Learn more about SolarReviews and how we make money.

When grid-tied solar panels make more energy than a customer needs, the excess is sent back to the electric grid along the same wires that carry power to the home when the sun is down.

Net metering is the utility billing practice of recording the excess energy generated by a solar installation and applying it to the customer’s bill as credit toward energy drawn from the grid.

It’s a pretty straightforward way to compensate solar panel owners for their contributions, and it’s been the law in many places across the United States for years. But like anything that involves utility companies or the law, there are nuances and complications that creep into the picture when you look a little deeper. And many states are starting to move away from net metering as the economics of participating in the grid get increasingly complicated.

Here’s our guide to net metering, including how it works, where it’s available, the benefits and drawbacks, and alternative billing programs.

Key takeaways

Net metering ensures that every kilowatt-hour (kWh) of energy a homeowner's solar panels produce goes toward reducing their utility bills by the same amount.

Programs differ in how long credits are allowed to roll over and how much value each credit has.

The benefits of net metering include good financial return on an investment in solar panels, simple billing arrangements, environmental benefits, and reduced costs of infrastructure and fossil fuel power plants.

Some utilities claim that net metering causes a “cost shift” and increases electricity rates for non-solar customers.

Many states have moved away from net metering in recent years, replacing it with net billing that offers lower credits for all kWh sent to the grid from solar owners’ systems.

How net metering works

The type of net metering described above is the simplest example of the practice and is also called “true net metering” or “1-for-1 net metering” because the utility offers credit for each kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity sent to the grid, which can be redeemed toward a kWh used when the sun isn’t shining.

When a homeowner gets a solar energy system installed, the utility replaces their electric meter with a new bi-directional meter, which can record the energy the solar panels export to the grid and the energy the customer takes from the grid when the solar panels aren’t making enough power to run the home’s appliances.

At the end of each billing period, the utility totals up the energy that was sent to the grid and energy used from the grid. If the homeowner used more electricity than they sent, the utility bills them for the difference. If they send more than they used, the utility records a credit balance that will be applied to the next monthly bill.

Here’s a graphical representation of how that works, with an increasing credit during the daylight hours that gets used up over the course of the night:

Not all net metering programs work in exactly the same way. Differences between net metering programs include:

Credit rollover (monthly vs. annual vs. indefinite)

Value of credits

Time of use rates

Net metering credit rollover

Under most net metering programs, kWh credits carry over from month to month, meaning credit for energy generated in sunny summer months can be used toward energy a customer purchases in darker winter months.

Some utilities allow these credits to carry over indefinitely, but most reconcile any credits that remain at the end of a 12-month period and pay the customer for them at a close-to-wholesale rate. This is called the “true-up date,” and it is generally set as the date a customer’s solar panels were given permission to operate (PTO) interconnected with the grid.

Some utilities allow solar customers to select their annual true-up date, while others set one date for all customers, which is usually in the late spring to give solar owners the best chance of using up any banked credits from the previous year before the next sunny season.

There are also places where net metering credits are reconciled every month. Any excess energy credits left at the end of each billing cycle are paid to the solar system owner, usually at a greatly reduced rate close to the wholesale price of energy. This reduces the financial benefits of net metering, and homeowners in these places may choose to design a solar system that won’t exceed their total usage in sunny months.

Value of net metering credits

Under true net metering, each kWh credit represents a kWh, and they can be redeemed for energy from the grid at any time. But some net metering programs provide a monetary bill credit instead. That credit can be exactly equal to the retail value of a kWh, but sometimes it can be less.

For example, under Net Energy Metering (NEM) 2.0 in California, the energy credits are worth just a small fraction less than the retail rate because of non-bypassable charges, which are portions of the retail cost of energy that go toward low-income and environmental programs.

Time of use rates

Some utilities offer time of use (TOU) rate plans, under which the cost of energy changes depending on the time it is used. Peak demand on the grid usually occurs in the evening on weekdays, when most people return home from work and begin using their appliances. During these times, the cost of energy increases.

TOU rate plans have at least two different rates for on-peak and off-peak times. Solar panel owners on TOU rates get credit for the electricity their panels send to the grid during the time period it is generated.

So for example, say a solar installation sends 10 kWh to the grid during the off-peak period when energy is $0.10/kWh. The owner would earn a $1 credit for that energy. If energy from the grid is worth $0.15/kWh during peak times, the credit they earned would only be able to offset about 6.7 kWh worth of peak-time electricity.

Because of the varying value of energy, TOU rates can make a home solar battery more financially beneficial. Homeowners can charge their battery with solar energy during the day, and use the stored energy in the battery to avoid paying peak energy prices in the evening.

Virtual net metering

Virtual Net Energy Metering (VNEM) is a system of distributing energy credits among members or subscribers of a shared solar array (often called a community solar farm). In other words, it’s a way for consumers to gain some of the benefits of solar energy without having to install their own solar system.

In virtual net metering, the solar panels typically aren’t connected to the meters of the subscribers. The shared system could be a solar panel system located in a common area of a condo or a large custom solar farm with hundreds of subscribers.

In most VNEM situations, the electricity produced goes straight into the grid in return for credits. Subscribers receive bill credits based on the amount of energy produced by their shares of a community solar installation.

Different subscription models are used for such projects. The subscriber can either rent a share of the panels or own them outright to become eligible for receiving credits on their electric bill.

The availability of VNEM is great news for consumers who can’t go solar themselves. As many as half of all consumers and businesses in the U.S. cannot have a solar panel system installed for various reasons, according to a 2015 report by National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and Department of Energy (DOE).

Benefits of net metering

There are many benefits of net metering, some of which go to the solar system owner and some of which go to the grid and society as a whole. Here’s a list of some of the benefits:

Makes solar more financially viable for homeowners

Provides a simple way to credit solar owners for the energy their systems produce

Encourages new solar development on existing structures, reducing carbon emissions and leaving existing undeveloped land untouched

Reduces the need for new fossil fuel power plants

Reduces the need for new power transmission infrastructure, which is expensive, controversial, and takes years to approve, fund, and build

Virtual net metering makes the benefits of solar available to people who don’t own their homes

Drawbacks and controversy

As solar advocates, we’d love to tell you that there are no drawbacks to net metering, but that wouldn’t necessarily be true. Studies have shown that solar is a net benefit to the grid when there is a small number of net metered systems interconnected, but things get more complicated once net metering hits a threshold of around 5% to 10% of peak demand.

Here are some of the drawbacks of net metering:

Without time of use billing, the value of net metering credits isn’t adjusted based on the time it’s produced.

Too many net metered solar installations reduce demand on the grid during the daytime, but don’t alleviate problems at peak evening times as the sun is setting.

When there are a lot of solar installations in a small area, the distribution grid sometimes needs to be upgraded to handle higher levels of the two-way flow of power, potentially costing all ratepayers more (although the cost often falls on the owner of the system that will cause the distribution system infrastructure to exceed its rated capacity).

Some utility companies claim that net metering represents a “cost shift” from wealthier people to lower-income people, because wealthier people can install solar panels and reduce their energy bills down to almost nothing, leaving people without solar to pay an increased share of the fixed costs of maintaining the grid.

The effects of the alleged “cost shift” are difficult to fully understand because the argument that a cost shift exists is mainly advanced by electric utility companies themselves. Over the past ten years or so, utility companies around the country have pushed the cost-shift narrative as a way to end net metering.

Often, these companies are simply trying to kill rooftop solar, and not trying to build a system that works to reduce bills for their ratepayers. They don’t attempt to offer a reasonable successor program that recognizes the full financial, environmental, and social benefits of solar to the grid, or they spend millions of dollars (sometimes ratepayer dollars) to lobby lawmakers and public utility commissioners to ignore many of those benefits.

Alternatives to net metering

There are a few different net metering alternatives in place around the U.S., including net billing, feed-in tariffs, and buy-all, sell-all. States like Arizona, Michigan and California used to have net metering but have since moved to so-called “successor” programs, while other states never had good policies to begin with.

Here’s a rundown of some net metering alternatives:

Net billing

Under net billing, solar energy that is used to power the home’s appliances directly reduces the homeowner’s electric bill by the full retail cost of electricity, but energy that is sent to the grid is credited at a lower rate. The monetary credits are applied toward the customer’s bill, but don’t usually equal the cost of the electricity the customer pulls from the grid when their solar panels aren’t producing energy.

Net billing is often combined with TOU billing, and the credits paid to solar owners for energy sent during the sunniest parts of the day are often very low, while the energy they have to buy from the grid in the evening is priced very high. Because of this, net billing encourages solar owners to add batteries to their systems, storing the solar energy instead of selling it for pennies on the dollar, and then using it in the evening instead of buying on-peak power from the utility.

California’s net billing is the most infamous example of this type of solar metering. In late 2022, the California Public Utilities Commission handed down a decision to switch the state away from its modified net metering system. The new Net Billing tariff has different payments for solar energy for each hour of the day, every day of the year, which change on a monthly basis. Many times during the year, the value of exported solar energy is almost $0.

Buy-all, sell-all

In a sort-of worst case scenario for home solar, you may be required to engage in “buy-all, sell-all” also known as “parallel operation” with the utility grid. “Buy-all, sell-all” means you buy all the energy you need from the utility company and send all the solar energy your system produces to the grid.

The price paid for solar energy under a buy-all, sell-all program is called the feed-in tariff. These programs usually pay a low price for every kWh of solar energy, compared to the price at which the utility sells electricity to residential customers.

Thankfully, there are very few places where solar owners are required to engage in buy-all, sell-all programs.

Solar self-consumption

Utility customers in many places can set up a special solar installation called a “non-export system.” That means you have to either use, store, or lose the solar power so it doesn’t get sent to the grid.

With a non-export system, you have to try to maximize your use of solar energy by installing batteries to store the excess electricity and reverse-power protection devices to prevent exporting power. You can still get power from the grid when you need it, too.

This type of system can get quite complicated, and when installed on a home with a grid connection, you’ll still need to notify your utility and likely pay an interconnection fee and/or other fees that the utility charges to ensure your system can be safely installed.

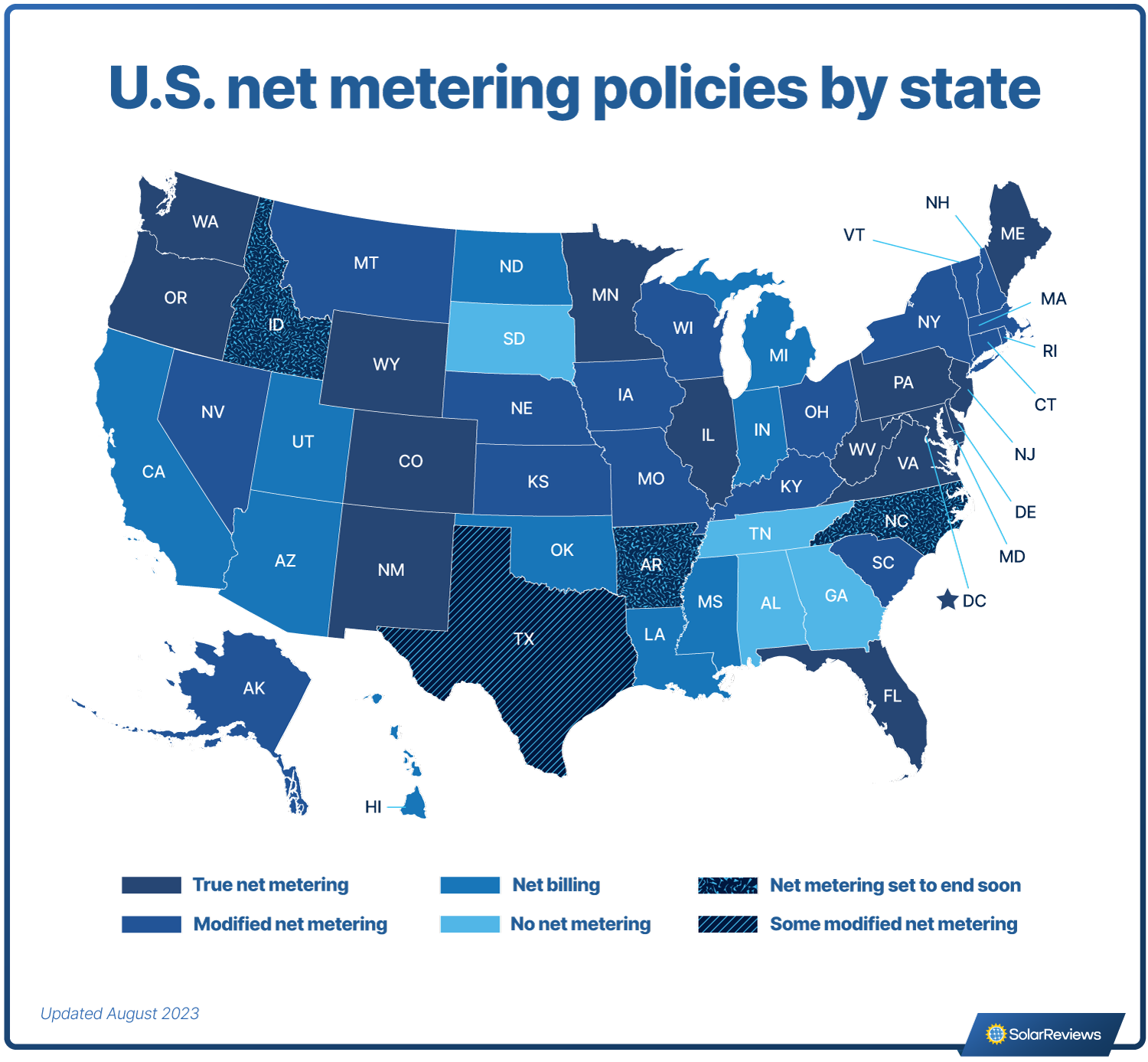

Which states have net metering?

The map below shows the states that offer true net metering, modified net metering, net billing, or no net metering as of June 2023.

Is net metering going away?

In recent years, most states have gone through the process of amending or even eliminating net metering rules, with mixed results.

Some states—like Connecticut, New Hampshire and Nevada—have come up with relatively smart “successor” programs that pay solar owners for each kWh based on a value of solar energy developed through careful study. In other states, solar owners are paid the wholesale price of energy (often a small percentage of retail), without regard for the benefits rooftop solar provides to the utility and its ratepayers.

Then there's California, which has really screwed things up (except for LADWP, which has retained net metering).

The difference has a lot to do with politics, lobbying, and the power of the almighty dollar, on both sides of the issue. As consumer advocates, we’re concerned with what’s best for the average homeowner who wants to install solar panels.

Three states have recently set deadlines to end their net metering programs, and homeowners in these places may want to get solar panels soon. Here’s a rundown of the details:

Idaho Power customers who install new solar panel systems are subject to changing rules, as the state Public Utilities Commission is in the process of allowing the company to offer decreased compensation for excess generation.

People in Arkansas will need to have solar panels installed by Sept. 30, 2024 to qualify for net metering.

After July of 2023, Duke Energy customers in North Carolina will no longer be eligible for net metering, but will be able to sign up for a somewhat similar “bridge rate” if they get solar panels installed by the end of 2026.

The most infamous case of a state amending its net metering rules happened in California in early 2023. Homeowners who get solar panels installed in California today have to sign up for a new version of solar compensation called Net Billing (also known as NEM 3.0). It results in an overall reduction in the value of excess solar energy credits, as well as a complicated system of hourly changes in export credits that is adjusted every month.

Whenever a state makes changes to its net metering system, we’ll keep you up to date on the SolarReviews blog.

Bottom line: why does net metering matter?

Net metering policies across the U.S. have been the single best incentive to get ordinary people to invest in renewable energy generation systems. That's why states like Florida, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin have protected net metering and reaffirmed its value. Even in states were net metering isn't required, some companies still offer it. For example, there are a number of solar buyback plans in Texas, even though there's no mandate for net metering!

Thanks to net metering rules, people all across the country can generate their own electricity and contribute to fighting climate change.

As the grid becomes more modernized and decarbonized, distributed generation assets like solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicles will become much more important, providing value to both system owners and the grid as a whole.

Ben Zientara is a writer, researcher, and solar policy analyst who has written about the residential solar industry, the electric grid, and state utility policy since 2013. His early work included leading the team that produced the annual State Solar Power Rankings Report for the Solar Power Rocks website from 2015 to 2020. The rankings were utilized and referenced by a diverse mix of policymakers, advocacy groups, and media including The Center...

Learn more about Ben Zientara