Find out what solar panels cost in your area

A Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) is a law that requires electric utilities in a state to generate a certain percentage of electricity from renewable sources by a certain date. If a utility company fails to meet these goals, it can be subject to large fines.

Because of those fines, utilities are inclined to offer perks to homeowners to meet the RPS targets. The RPS is also used to determine the amount and type of incentives available for solar buyers. 24 states (including the District of Columbia) have current RPS laws, and an additional 7 states had RPS laws that have passed their target dates.

Finally, 6 states have current or former voluntary renewable energy goals instead of mandates.

That’s about as simple as we can put it. But as you might imagine, an RPS can get quite complicated. Below, we’ll get into how RPS laws work, how they vary from state to state, and what the best states are doing to encourage renewable energy growth.

Why are Renewable Portfolio Standards important?

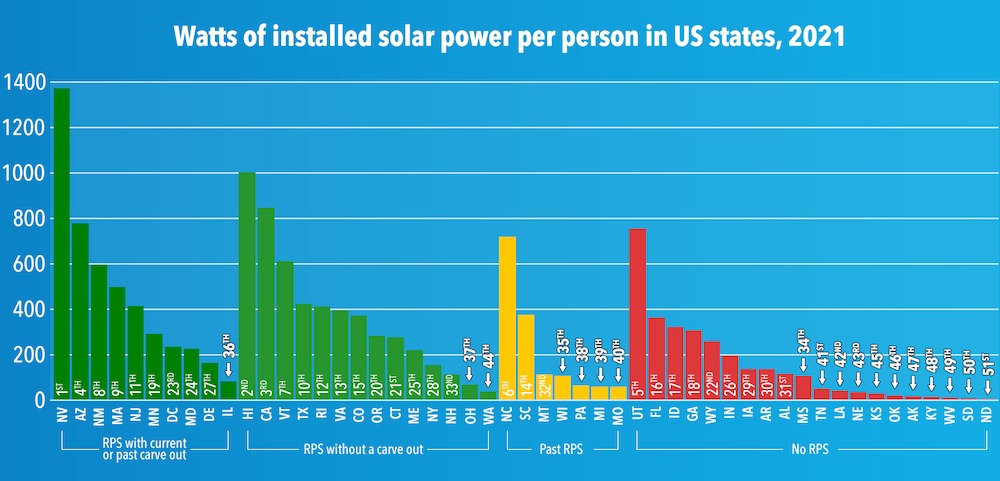

24 states (including Washington DC) have non-voluntary RPS laws. All but one of the top 10 states for solar (per capita) have active or former RPS laws. In fact, of the top 25, only 5 have no form of RPS at all, and they’re all either very sunny or very low-population states. Check out this chart:

That said, RPS laws are becoming less essential to spur solar development. The costs to install solar have fallen precipitously in the past decade, and that’s made them more financially viable in those sunny states.

How RPS laws work

In general, an RPS law is set up to require utility companies to generate either a certain percentage of their total electricity or a certain amount of power capacity (measured in megawatts ) from renewables. The goals are set by lawmakers working with experts from the scientific and energy communities, to come up with targets that are realistic but strong.

Typically, the main goal is set for several years in the future, with interim goals for years in between. For example, California has a goal of 100% of retail energy sales by 2045, with increases of 5-8% every 4 years or so between now and then. Each time a new interim deadline arrives, the state enforces compliance, which means they assess fees to the utilities that haven’t met the goals.

Eligible technologies

Each state gets to define the kinds of electricity generation that qualify as “renewable.” Nearly all count solar, wind, and geothermal power generation, but other technologies aren’t as widely included. Hydroelectric power, for example, is sometimes dis-included from a state’s RPS because of its relatively high impact on the environment, and sometimes simply because the power already existed as part of the state’s energy mix when the RPS was enacted.

Some states include specific goals for certain kinds of renewable generation, especially solar. When this kind of technology-specific goal is mandatory, it is called a “carve-out” or “set-aside,” and it comes with its own set of rules, which we’ll cover in another article.

One important term when it comes to eligibility is “distributed generation,” or “distributed energy resources,” which basically means small electrical generation systems spread around a utility service area. These resources include wind power turbines, solar panel systems, and small hydro generators, but can also come from non-renewable sources.

Distributed resources have certain benefits to the electrical grid, such as reducing the need for expensive transmission line upkeep and increasing reliability of the grid. Because these benefits go hand-in-hand with small renewables, specific goals for distributed generation are often included in RPS laws.

Renewable incentives

A major feature of RPS laws is the creation of incentives for renewable technologies. These incentives are basically subsidies, either from tax dollars within the state or from utility companies, which offer rebates to their customers as a way to encourage them to install solar panels or wind turbines and contribute to the overall RPS goal. The utility companies often recoup the costs of the rebates through additional charges to all customers (often fractions of a penny per kilowatt-hour of energy, and totaling less than $10-$20 per year, per household).

The most popular types of solar incentives defined via RPS are solar rebates, tax credits, and Renewable Energy Credits.

Rebates work just like a cash-back offer when you buy an efficient appliance—you get money back from the utility or the government when you buy a renewable system. But in the case of renewable systems, the amount of the rebate often goes to reducing the price you actually pay for the system, instead of coming back as a check after installation.

Tax credits, on the other hand, give renewable system owners cashback in the year after they install the panels. Offers vary widely by state but generally allow for the owner to receive a credit equal to a certain percentage of the cost of their system. They often have caps on the amount an owner can receive, and also offer carryover of parts of the credit to the next year(s) if the owner can’t claim the whole amount in one year.

Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) are a bit more complicated. A renewable energy system earns its owner one REC for each megawatt-hour (MWh) of electricity it generates. The REC serves as “proof of generation,” which can then be sold to a utility company to help it meet its goals under the RPS.

Unlike a rebate or tax credit, a REC is a way for system owners to earn additional money as their system actually produces electricity. The price of RECs varies widely across the country, from almost nothing to hundreds of dollars, and depends on several factors we cover in a special article about RECs. This kind of market-based incentive can be offered for a limited time (e.g., the first 5 years of electricity production) or on an ongoing basis.

Not all RPS laws include incentives, and many solar incentive programs are passed through separate legislation or utility commission decisions. As we mentioned above, the cost of these subsidies is paid either with state funds (taxes) or by utility companies, which are often allowed to recoup the cost of the incentives through small fees on all of their customers.

Ways in which RPS laws vary

RPS laws can vary widely in a number of ways. States craft their RPS laws to meet their specific needs, including current energy mix, resource availability, and economic landscape. Like any big piece of legislation, lobbyists often have a say in the process, even recommending or writing specific clauses to be included.

The biggest variation between states can be seen in the renewable goal and timeframe for reaching it. For example, Michigan once had a goal of 10% renewable energy by the end of 2015, while Hawaii has a goal of 100% renewable energy by 2045.

Another major way state RPS laws differ is how they apply their standards to different kinds of utility companies. Many states have lower standards for smaller Publicly Owned Municipal Utilities (POUs) and electric co-ops, and higher standards for large investor-owned utilities (IOUs).

For example, California‘s RPS calls for 100% of the electricity sold by each utility in the state to come from renewable sources by December 31st, 2045. The mandate is the same for both Investor-Owned Utilities (IOUs) and Publicly Owned Municipal Utilities (POUs). Conversely, Minnesota has an RPS mandating 31.5% of all electricity generated by the state’s big IOU, Xcel Energy, come from renewables by 2025. POUs and other smaller utilities and co-ops are only required to generate 25% from renewables by the same deadline.

All state RPS laws

Below, we’ve included an alphabetical list of all the states with current RPS laws, not including those with voluntary goals instead of binding targets.

State | Target | Date |

|---|---|---|

Arizona | 15% | 2025 |

California | 100% | 2045 |

Colorado | 100% | 2050 |

Connecticut | 48% | 2030 |

Delaware | 40% | 2035 |

Hawaii | 100% | 2045 |

Illinois | 100% | 2050 |

Maine | 100% | 2050 |

Maryland | 50% | 2030 |

Massachusettes | 40% | 2030 |

Minnesota | 27% | 2025 |

Nevada | 50% | 2025 |

New Hampshire | 25% | 2025 |

New Jersey | 50% | 2030 |

New Mexico | 100% | 2020 |

New York | 100% | 2030 |

Ohio | 8.50% | 2025 |

Oregon | 50% | 2040 |

Rhode Island | 39% | 2035 |

Texas | 10000 MW | 2025 |

Vermont | 75% | 2032 |

Virginia | 100% | 2050 |

Washington | 100% | 2045 |

Wisconsin | 100% | 2032 |

Ben Zientara is a writer, researcher, and solar policy analyst who has written about the residential solar industry, the electric grid, and state utility policy since 2013. His early work included leading the team that produced the annual State Solar Power Rankings Report for the Solar Power Rocks website from 2015 to 2020. The rankings were utilized and referenced by a diverse mix of policymakers, advocacy groups, and media including The Center...

Learn more about Ben Zientara