Updated 1 year ago

Is net metering still necessary in 2023?

Written by Ben Zientara Ben ZientaraBen Zientara is a writer, researcher, and solar policy analyst who has written about the residential solar industry, the electric grid, and state util...Learn more , Edited by Catherine Lane Catherine LaneCatherine has been researching and reporting on the solar industry for five years and is the Written Content Manager at SolarReviews. She leads a dyna...Learn more

Why you can trust SolarReviews

SolarReviews is the leading American website for solar panel reviews and solar panel installation companies. Our industry experts have a combined three decades of solar experience and maintain editorial independence for their reviews. No company can pay to alter the reviews or review scores shown on our site. Learn more about SolarReviews and how we make money.

For many years, net metering has been the single most important policy for rooftop solar owners, ensuring that every kilowatt-hour of electricity their panels generate reduces their energy bills by the full retail value of a kWh charged by their utility.

Recently, several trends have conspired to change the landscape. Electricity prices have increased faster than historical averages, the cost of batteries has come down, smart EV chargers make it easier to use solar energy in your home, and many homeowners can now earn ongoing payments for participating in a virtual power plant.

All these things mean that installing solar panels on your home or business is more financially advantageous than ever before, even if you can’t get true 1-for-1 net metering.

But does that mean net metering is no longer necessary? Let’s examine how the grid's changing economic landscape has changed this longstanding program's value.

Key takeaways

Net metering is great because it’s a simple way to reward the owners of rooftop solar systems for the benefits they provide to the grid.

The benefits of solar are often more valuable than the retail cost of electricity, meaning that offering net metering to owners of small solar systems represents a net positive to society.

Utility companies have become adept at painting solar owners as grid users who don’t pay their fair share of the cost to maintain it, and they’ve been successful in ending net metering in some states.

For people who live in non-net metering states, there are many options to increase self-consumption of solar power, including batteries, smart appliances, and smart EV chargers.

Although metering’s importance has slightly diminished, it remains the gold standard of solar policies for its simplicity and predictability.

Why net metering is so good

When net metering was first conceived in the late 1970s, it was based on a simple premise: if a solar energy system that was installed on a grid-connected building ever produced more energy than the building could use, the meter would spin backward as the solar energy was sent out along the same lines that carried power into the building at other times.

That simplicity benefited both solar owners and utility billing departments, but it wasn’t necessarily nuanced enough to account for the benefits the solar owner was providing to their neighbors and the grid. Those benefits are more significant than anyone could guess back in the ‘70s.

Nowadays, many recognize that the benefits of net metering include:

Avoided costs of purchasing generated energy and building large-scale generation capacity

Avoided transmission and distribution costs and lost energy from long-distance transmission

Reduced costs and uncertainty from fuel hedging

Reduced spending on grid operations and maintenance

Health benefits from reduced particulate and greenhouse gas emissions

Reduced environmental costs associated with climate change

Increase in jobs and benefits to the local economy

The first four benefits listed above go to utility companies and grid operators, and the final three improve society as a whole. Studies that look at all of these benefits show that solar provides more value to the world than the retail cost of electricity, which generally means net metering is a win-win. A final benefit is that solar owners can easily predict how their investment will pay back its cost.

Criticisms of net metering

Some factual arguments against net metering make sense. For example, it is true to say that ordinary net metering doesn’t assign value to exported solar energy based on the time it’s exported. More and more, the grid needs power at specific times in the evening when demand is highest, and solar panels produce the most power during the day when demand is low.

Unfortunately, the only fact most utility companies seem to care about is that they're losing revenue. Led by trade groups like the Edison Electric Institute, electric utilities across the country have banded together to attack rooftop solar, advancing the argument that net metering allows solar owners to benefit from the grid while paying none of the fixed costs to maintain it.

On their face, this idea might seem to have merit. After all, net metering allows many solar owners to essentially eliminate their electricity bill; a solar system that fits on a residential rooftop can often produce all the energy consumed by the home’s occupants in a year, meaning the owners might end up paying just the small monthly connection fee of around $10 (some places charge more, but $10 to $15 per month is average).

But these arguments rely on fuzzy math put forth by industry analysts who conduct “value of solar” studies that don’t include all the benefits listed earlier. These analysts are often hired by state public utilities commissions (PUCs) to perform these studies, with specific instructions about which costs and benefits they should consider.

In most states, PUC commissioners are appointed by the governor and are often ex-employees of the very utility companies they are charged with regulating. They are not, as a rule, unbiased arbiters of truth and justice.

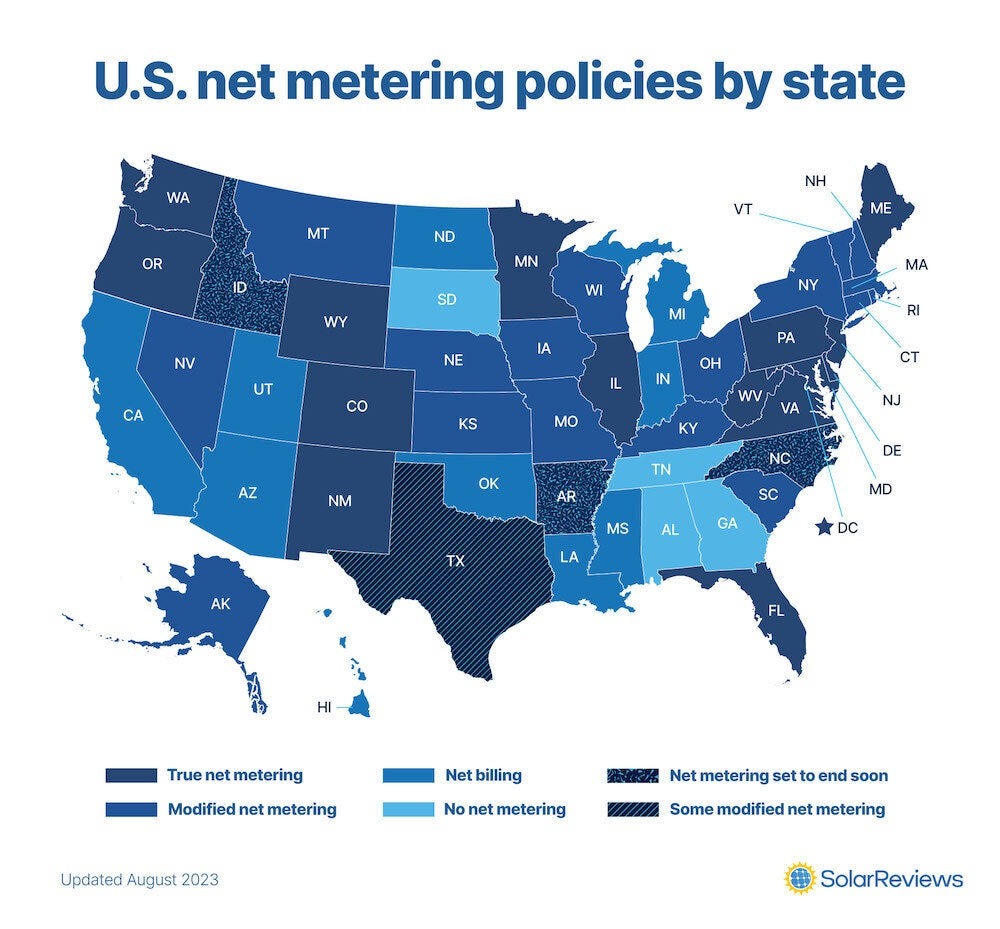

The effects of the coordinated campaign to kill rooftop solar include the end of net metering in many states, reduced compensation for excess solar energy, and increased fees and roadblocks to get small-scale solar connected to the grid. In part because of these efforts, 14 states have no net metering, and three other states have near-future deadlines when a successor will replace the program.

Most famously, California recently replaced its longtime Net Energy Metering rules with a program called Net Billing (aka NEM 3.0), which greatly reduces compensation for exported solar energy except for a few hours per year when power is in very high demand.

Fourteen states don’t offer net metering, with three more set to join them soon.

That last point actually provides a bit of hope because it points to one way net metering can be updated to be more equitable. Exporting energy at times of high demand on the grid is very good, and batteries can help ensure that excess solar energy is stored for when it’s needed the most. But there are other ways to use that extra energy, too.

Ways net metering is becoming less crucial

It’s 2024, and several states without net metering still have robust solar marketplaces. Texas, Nevada, Arizona, and Hawaii all have little to no net metering and still offer good savings with solar power. These places have a few things in common: relatively high electricity prices and a good amount of sun.

Where electricity prices are high, you can easily save a lot of money with solar. And even in places with moderate electricity prices, you can maximize your self-consumption of solar energy and still save a lot. Every kWh of solar energy you produce and use in your home still reduces your bill by the full cost of a kWh.

Have you seen these electricity prices lately?

Electricity has become much more expensive in the last few years. In the most extreme case, National Grid warned of 64 percent increases in New England in 2022. Many reasons—especially the prices of natural gas and fuel oil increasing due to the war in Ukraine—are responsible for nationwide electricity costs increasing by double the historical annual average after accounting for extreme inflation.

These price spikes have significantly increased the cost of electricity for most people, and have caused interest in solar to skyrocket. If your cost per kWh goes up over 60%, you might be okay with not getting the full credit on the kWh you export to the grid. But maximizing your usage of the solar energy you generate is always a good choice.

The connected world offers opportunities

Our modern, always-connected world provides many opportunities to improve how we use electricity, especially for solar panel owners. While the solar-only rooftop systems of the past couldn’t help but export excess energy at the moment it was produced, the smart home appliances of today can help homeowners make full use of their solar energy.

Remember: even in non-net metering states, you save the full retail amount on any energy you produce and use to power your home. By employing the strategies listed below, solar owners can avoid exporting most or all of their electricity, thereby saving themselves more money in a state without net metering.

Here are several ways homeowners can now use solar energy in their homes and avoid sending it to the grid in exchange for pennies on the dollar in compensation:

Activating smart HVAC systems to run on excess solar energy and pre-cool spaces before times of peak demand

Activating water heaters when solar panels produce more energy than necessary

Using excess solar power to charge an electric vehicle, smart EV chargers can send all excess solar energy to the car’s battery rather than onto the grid

Storing electricity in batteries and discharging those batteries to avoid peak charges on a time-of-use electric rate

Participating in a virtual power plant and earning payments for providing services to the grid during times of peak demand

There are already companies making technological solutions to help people maximize their use of their own solar energy, and before long, these kinds of smart energy management systems will be the default for new homes and retrofits.

VPPs will save the grid

As far as virtual power plants (VPPs) are concerned, the possible savings are immense. Here’s how it works: participants store solar energy in batteries, which are activated during times of peak demand by either the utility company or a third-party called an aggregator. When batteries from hundreds or thousands of utility customers are activated at the same time, it can equal as much power as a large-scale natural gas power plant.

When utilities have to purchase power on the fly during those peak times, it can get very expensive. A VPP prevents utilities from paying dozens of times the retail rate for power from a fossil fuel generator. This saves everyone money and saves the planet, too, by avoiding the need to use inefficient “peaker” plants for power.

VPPs are available in many states now, and new programs are opening all the time. VPP participants can get paid quite a lot of money for their excess energy in parts of California, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Texas. Read more about solar battery incentive programs near you.

Bottom line: Why net metering still matters

Everything we’ve laid out above shows that net metering is less important than it used to be, at least in states with high electricity prices or where smart controls can be added alongside solar to economically maximize self-consumption.

But that doesn’t mean that net metering is no longer crucial; its benefits are still readily apparent. Net metering still offers a straightforward way to reward solar owners for providing benefits to the grid and society as a whole. Humanity needs all the carbon-free energy generation we can manage, and offering kWh offsets to people willing to invest their own money in a clean energy source is still one of the simplest, best ways to install it.

It’s especially clear that the benefits of offering net metering still outweigh the costs of lost utility company revenue. We need to change the way our electric grids work and create interactive, responsive systems that blend into everyday life as they reduce costs and carbon intensity for all of society. Net metering is still necessary to move us closer to that future.

Ben Zientara is a writer, researcher, and solar policy analyst who has written about the residential solar industry, the electric grid, and state utility policy since 2013. His early work included leading the team that produced the annual State Solar Power Rankings Report for the Solar Power Rocks website from 2015 to 2020. The rankings were utilized and referenced by a diverse mix of policymakers, advocacy groups, and media including The Center...

Learn more about Ben Zientara